All text here is written by Anders Lindqvist (breakin).

Before Early Days (early 2013)

When I was starting with SNES-things I thought I wanted to do a game. The dream was to make something Zelda-like since Zelda for the SNES was my all time favorite game growing up. I quickly realized that since the SNES had such a good graphics chip you needed actual graphics. I thought I could maybe borrow the graphics from Zelda itself while making my engine/editor. To bootstrap myself. I found map data online but it didn’t have unique tiles due to animations. Then I found a convertor that extracted the graphics but somehow it didn’t feel satisfying using it. Would it perhaps feel better if I extracted it myself?

At the same time I was writing a very small game; a clone of the Lady Bug.

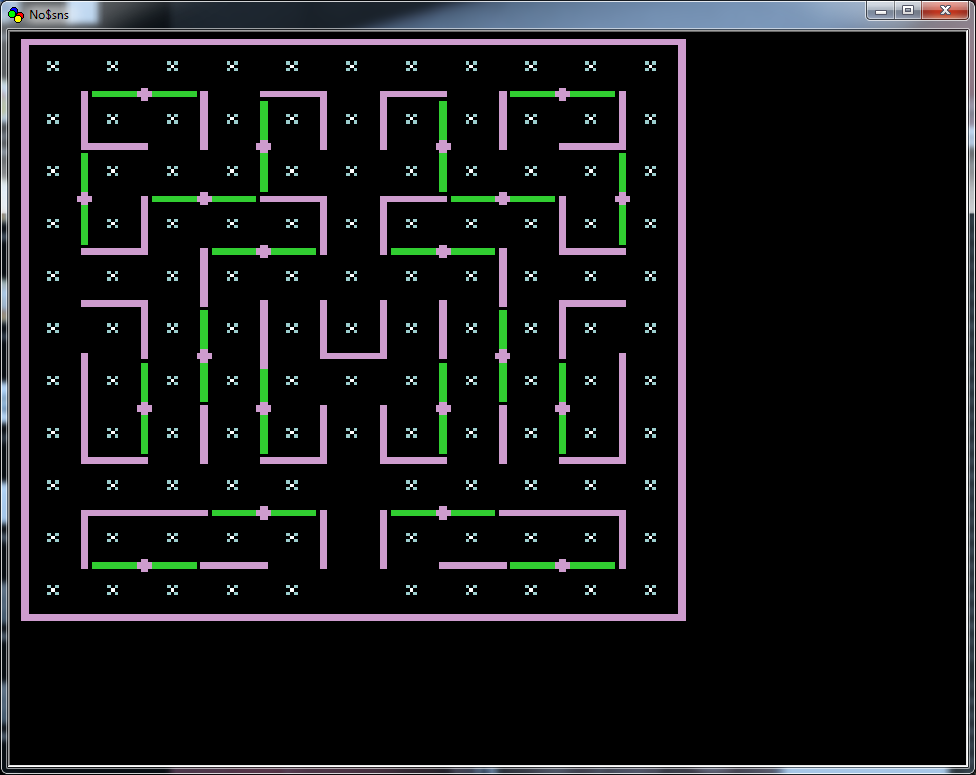

It was the game me and my wife played the most while visiting Barcade in New York. I never completed making this game, this static screen on the first level was as far as I got:

Here is the tile set I created (note that SNES has X- and Y-mirror flags per tile so no mirroring here):

Trying to make the Lady Bug clone made me realize that I really wasn’t a good 65816 programmer. At least not yet. Some times when you are bad at something you blame the tools but in my case I simply blamed inexperience. I felt like I needed to see the source code of something bigger than the tutorials I have seen. To get a feeling for how you organized something like a game. Something like Zelda…

Reverse Engineering Zelda

I didn’t realize it at the time but I was slowly gravitating towards making tools. Reverse engineering Zelda was the catalyst.

My idea was that while I was a SNES novice I was an expert C++ programmer and I could probably come up with powerful ways to break the game apart. There is no better way to truly understanding something than to write everything yourself. NIH might be strong with me but I sometimes feel that it is justified.

While higan was the best emulator, there were other tools I loved more when it came to reverse engineering. I used no$sns and a special version of snes9x where Geiger had added debug output. It was the latter which got snestistics started. It supported writing each instrution executed into a text log, something I could parse a build tools around. Geiger’s modifications seems to still be part of the offical snes9x repository but afaict it doesn’t compile anymore. There are now nice debugging capabilities for bsnes (old name of Higan) that didn’t exist back in 2013.

I wrote a python script that parsed the source code line-by-line. There was a lot of swearing involved since the log was text and in free form and there was many types of lines.

First Prototype

My first idea was that maybe the game was split into functions (ranges of instructions) and using the jumps between such fragments I should be able to do a visual representation. I used graphviz to generate a graph from all fragments. It turned out into an unreadable mess and this was a total failure. I tried many ways to make it compreshensible but I could finish it. Now after gaining a little bit of wisdome I know that the level I worked on was too low; you need to group many fragments of instructions into functions before trying to turn it into a graph. Now I think it would be quite possible to revist this idea, at least for a restricted set of functions being called during one frame.

Second Prototype

I gave up on trying to do a visual representation and instead tried to get the actual assembler source code for all code that was executed in my session. To print pretty assembler code I needed to decode the ROM data. To do that I needed to know where instructions were and how big they were. On the 65816 they are a number of modes that affect instruction size; index flag, memory flag and emulation flag. Emulation flag controls a 6502 backwards compatible mode of the CPU. The index and memory flags controls the register sizes of the index registers and the accumulator. Depending on the index size and accumulator size instruction could have different sizes (especially if an immediate value was stored with the instruction).

I had used WLA DX to do my small game prototypes and so I decided to use WLA DX for output. My goal was to be able to assemble my source code on-top of the original ROM that I had extracted from my cartridge without having any difference at all. Since WLA DX had good patching support these features was quite easy to setup. It took my quite a while to reach my goal but I eventually succeeded. I had the full source code (for the portions I played) but I had something else as well.

I had added the ability to name a program counter with a label name. Also, knowing where all jumps went, I had a lot of information about the nature of indirect jumps. Instead of

/* 801000*/ jml [123]

I got

jml [123] ; move_enemy_a

; move_enemy_b

; move_enemy_c

; move_enemy_d

I could add comments saying, in the source code, where things went. This made it much more readable. I also added an anonymous label wherever a jump went. That made it quite easy to search around the source code. I quickly started to understand what many functions in Zelda did.

Getting into the Fast Lane

At some point while writing my prototypes I discovered the following things:

- The Geiger output missed some things I needed

- I couldn’t transcribe it into a fully compatible WLA-DX assmebler source instruction in a lossless fashion. I think some addressing modes didn’t output all needed information.

- I didn’t really need a full log of everything that happened. I only needed to know what instructions were run ONCE not when and how many times. And also some jump information. So the logs were needlessly big!

- Parsing gigabytes of source in python can be slow! I’m really not great at writing high performance python (if that is even possible!)

But I was hooked at this point and I looked for a way around my text log / python problems. It turned out that I could get full snes9x source from github and build it for Windows quite easily. After looking at the source for a while I found a way to call a function for each 65716-instruction being called. I recorded where each instruction started and the value of the flags that affected instruction decoding (index, memory and emulation). Duplicates were ignored. After some more tinkering I could also save all jumps (jump at program counter X going to Y). When snes9x was exited I saved this dump. No matter how long I played the game this dump would be very small on disk and fast to parse since instruction running each frame would be the same and thus only saved once. Another nice thing was that my tool still didn’t have to understand the CPU at all since the emulation still happened in snes9x.

Super Famicom Wars

WIP.

Adding Emulation

In the beginning snestistics was quite simple. The emulator knew about how the SNES CPU works and ran the code. It simply saved down at what program counters operations existed at and also the flags that affects instruction sizes/interpretation. This was very simple and worked for all games. Later when adding features such as the trace log snestistics needed to be able to actually replay the stream of operations. That is it needed to know the order they were executed in. To support this - and some other cool upcoming features - a CPU-emulator was added to snestistics. It is not complete yet and some features are missing, but thanks to this it is now possible to do tracelogs, change annotations and then generate a new tracelog quickly without involving the emulator.

Adding a Scripting Language

WIP.