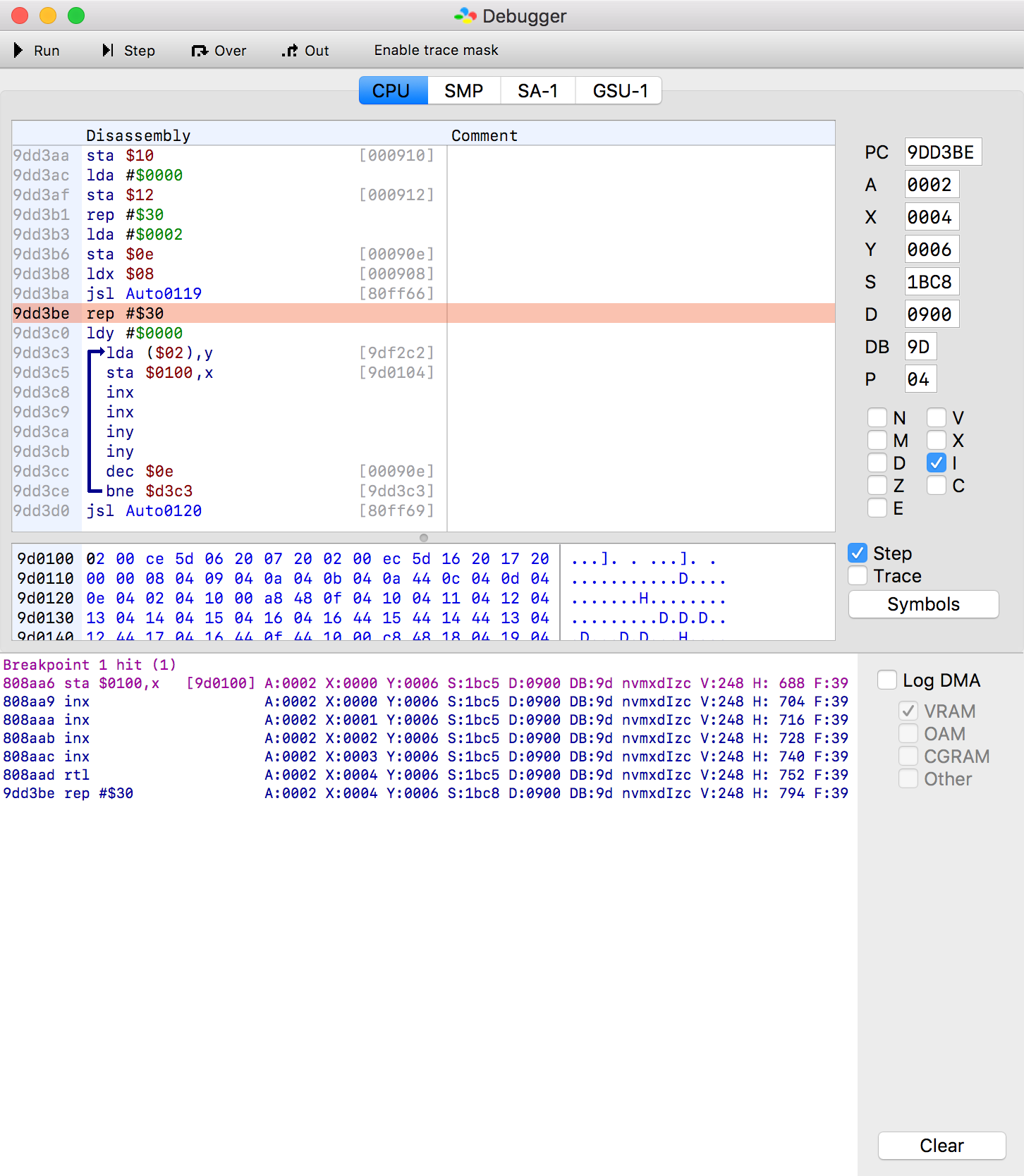

In the last post we used a combination of emulator debugging and snestistics disassembly to track down and understand the function responsible for putting new characters into the tile map. It turned out that it was a “system” function that is called each vertical blanking interval, and that “user” code elsewhere in the program must be feeding it data at the fixed RAM location $0100. Let’s put a write breakpoint there and run the text writer!

Breakpoint 1 hit (1)

808aa6 sta $0100,x [9d0100] A:0002 X:0000 Y:0006 S:1bc5 D:0900 DB:9d nvmxdIzc V:248 H: 680 F:13

That’s promising. Let’s continue running and see if any other code writes to this location.

Breakpoint 1 hit (2)

808aa6 sta $0100,x [9d0100] A:0002 X:0000 Y:0006 S:1bc5 D:0900 DB:9d nvmxdIzc V:248 H: 656 F:29

Nope! Only the instruction at 808aa6 touches RAM location $0100 during this screen, and is run only when a new character is plotted. Let’s search for 808AA6 in our disassembly!

Auto0015:

/* MI 808A70 C2 30 */ rep.b #$30

/* MI 808A72 48 */ pha

/* MI 808A73 E2 20 */ sep.b #$20

/* mI 808A75 2C 80 02 */ bit.w $0280 ; 7E0280 [DB=80]

/* mI 808A78 10 0D */ bpl.b _Auto0015_808A87

_Auto0015_808A7A:

/* MI 0900 808A7A E2 20 */ sep.b #$20

/* mI 0900 808A7C A9 01 */ lda.b #$01

/* mI 0900 808A7E 22 03 FF 80 */ jsl.l Auto0109

/* mI 0900 808A82 C2 30 */ rep.b #$30

/* MI 0900 808A84 68 */ pla

/* MI 0900 808A85 80 E9 */ bra.b Auto0015

_Auto0015_808A87:

/* mI 808A87 C2 20 */ rep.b #$20

/* MI 808A89 29 7F 00 */ and.w #$007F

/* MI 808A8C 0A */ asl A

/* MI 808A8D 18 */ clc

/* MI 808A8E 6D 8E 02 */ adc.w $028E ; 7E028E [DB=80]

/* MI 808A91 C9 3A 01 */ cmp.w #$013A

/* MI 808A94 B0 E4 */ bcs.b _Auto0015_808A7A

/* MI 808A96 E2 20 */ sep.b #$20

/* mI 808A98 38 */ sec

/* mI 808A99 6E 80 02 */ ror.w $0280 ; 7E0280 [DB=80]

/* mI 808A9C C2 20 */ rep.b #$20

/* MI 808A9E 8A */ txa

/* MI 808A9F AE 8E 02 */ ldx.w $028E ; 7E028E [DB=80]

/* MI 808AA2 9D 02 01 */ sta.w $0102,x ; 7E0102 [DB=80 X=0, 1C, 24, 38, 44, 48, 54, 6C, 70, 88, 8C, 90, A4, A8, B4, C0, C4, CC, D8, DC, E0 and 1 more]

/* MI 808AA5 68 */ pla

/* MI 808AA6 9D 00 01 */ sta.w $0100,x ; 7E0100 [DB=80 X=0, 1C, 24, 38, 44, 48, 54, 6C, 70, 88, 8C, 90, A4, A8, B4, C0, C4, CC, D8, DC, E0 and 1 more]

/* MI 808AA9 E8 */ inx

/* MI 808AAA E8 */ inx

/* MI 808AAB E8 */ inx

/* MI 808AAC E8 */ inx

/* MI 808AAD 6B */ rtl

Auto0016:

/* MI 808AAE A9 00 00 */ lda.w #$0000

/* MI 808AB1 9D 00 01 */ sta.w $0100,x ; 7E0100 [DB=80 X=1C, 24, 26, 38, 44, 48, 54, 6C, 70, 88, 8C, 90, A4, A8, B4, C0, C4, CC, D8, DC, E0 and 3 more]

/* MI 808AB4 8E 8E 02 */ stx.w $028E ; 7E028E [DB=80]

/* MI 808AB7 E2 20 */ sep.b #$20

/* mI 808AB9 0E 80 02 */ asl.w $0280 ; 7E0280 [DB=80]

/* mI 808ABC 6B */ rtl

The function labelled Auto0015 in the current disassembly writes the values in A and X to to $0100,x and $0102,x respectively, using the value in $028E as index. We clearly want to see where this function is called from.

I also included the following function, Auto0016, since it is likely that it probably also plays a part in populating the data structure consumed by NMI_vram_memcpy. Seeing that it writes a zero word to the data indexed at $0100, it is probably used to terminate the data. Now is a good time to move these two function from the auto.labels file to our organized label file. Although we do have a pretty good hunch on how they are used already, I’ll wait with renaming them for a bit.

Also worth noting is that Auto0015 increments X by 4 just before returning, making $0100,x point to the word after the two words written in the function. Since X isn’t stashed away anywhere, we should look closely at how X is used right after Auto0015 has returned to caller.

Following the Thread

Now let’s step out of the Auto0015 function and see where we end up!

Pro-Tip! Notice that the same labels we know from the snestistics disassembly are also visible in the bsnes+ debugger? Wonderful, right? Use the

-symbolfmaoutfileoption to generate a symbol file that will automatically be used by the debugger, if it’s in the same directory as the ROM file and has the same base name.

What’s immediatly striking is that the subroutine call we returned from wasn’t Auto0015 at 808A70, but rather another auto-generated function at 80FF66. Let’s quickly consult our disassembly to see what’s up there:

Auto0118:

/* ** 80FF60 4C CC 89 */ jmp.w Auto0014

.DB $4C,$EC,$89

Auto0119:

/* MI 80FF66 4C 70 8A */ jmp.w Auto0015

Auto0120:

/* MI 80FF69 4C AE 8A */ jmp.w Auto0016

Phew, nothing more complicated than a list of jumps. This technique was probably utilized to minimize build times; some (probably the “library/system”) functions are called through a list of jumps at fixed addresses, so the developers could more easily split up the build process into smaller chunks. Static library linkage, of sorts. Let’s move Auto0119 and Auto0120 from auto.labels and put them next to Auto0015 and Auto0016.

Now, back to the disassembly! The function around 9DD3BA is pretty long, ranging 218 bytes from 9DD36F to 9DD449, so I won’t list the whole thing here. But looking just at the same portion that was already visible in the debugger view above, we should be able to figure some things out:

_Auto0501_9DD3B1:

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3B1 C2 30 */ rep.b #$30

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3B3 A9 02 00 */ lda.w #$0002

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3B6 85 0E */ sta.b $0E ; 7E090E [DP=900]

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3B8 A6 08 */ ldx.b $08 ; 7E0908 [DP=900]

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3BA 22 66 FF 80 */ jsl.l Auto0119

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3BE C2 30 */ rep.b #$30

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3C0 A0 00 00 */ ldy.w #$0000

_Auto0501_9DD3C3:

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3C3 B1 02 */ lda.b ($02),y

; indirect base=000902, DP=900, DB=9D Y=0, 2

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3C5 9D 00 01 */ sta.w $0100,x ; 7E0100 [DB=9D X=4, 6]

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3C8 E8 */ inx

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3C9 E8 */ inx

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3CA C8 */ iny

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3CB C8 */ iny

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3CC C6 0E */ dec.b $0E ; 7E090E [DP=900]

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3CE D0 F3 */ bne.b _Auto0501_9DD3C3

/* MI 9D 0900 9DD3D0 22 69 FF 80 */ jsl.l Auto0120

Remember that Auto0119->Auto0015 returned with X indexing right after the two word values it had written at $0100 and $0102? The short loop that follows will read values indirectly from ($02),y and write them to $0100,x, calling Auto0120->Auto0016 when done.

My hunch was that Auto0015 would set up part of the data structure needed by NMI_vram_memcpy and returning with X pointing to the next location in that structure; where the actual values to be copied should go. Writing to $0100,x would then be used to insert tile values to be copied, followed by a call to Auto0016 to terminate the structure.

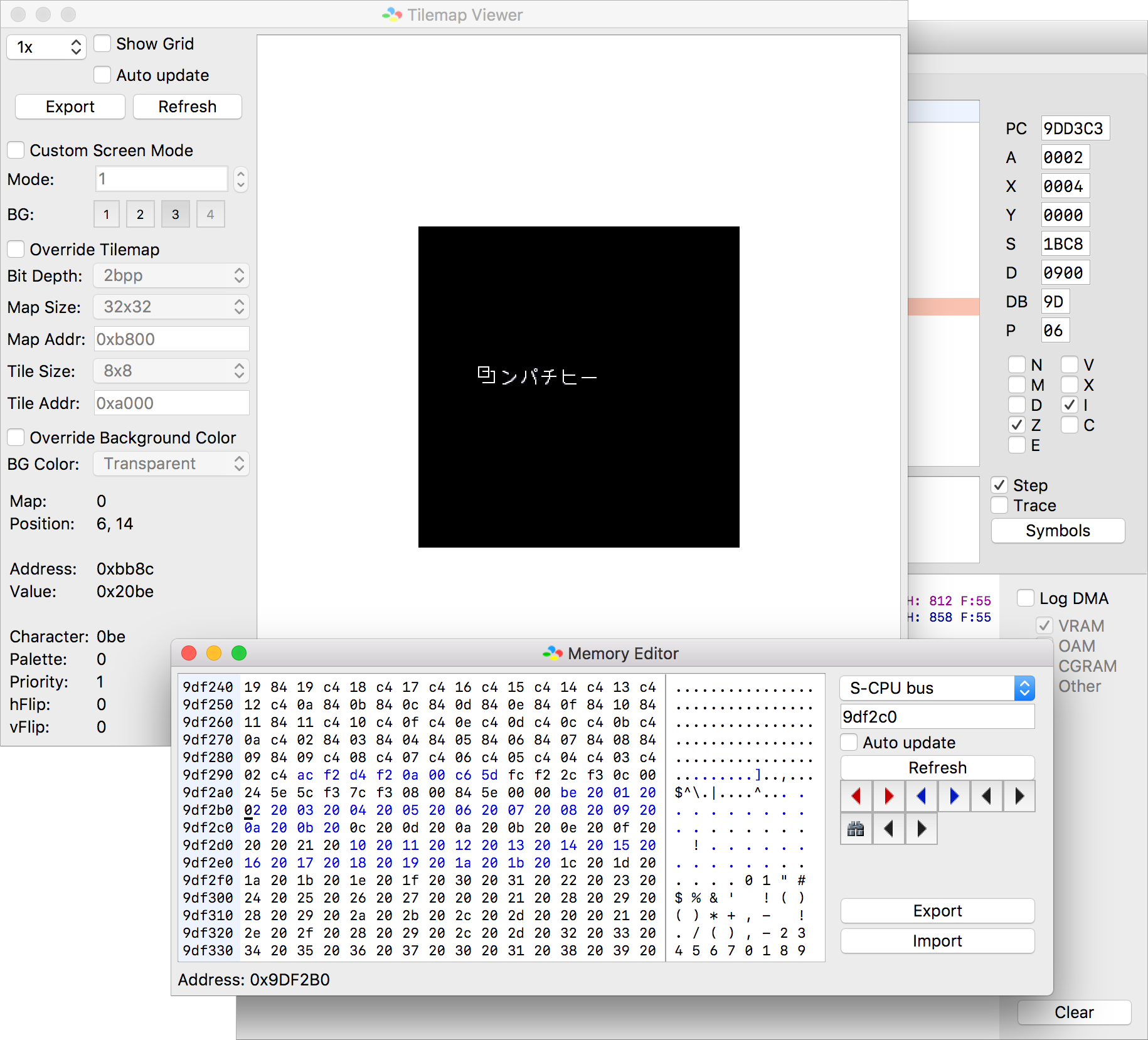

Let’s step through a couple of iterations at 9DD3C3 to see where it pulls data from.

Breakpoint 3 hit (1)

9dd3c3 lda ($02),y [9df2c0] A:0002 X:0004 Y:0000 S:1bc8 D:0900 DB:9d nvmxdIZc V:248 H: 812 F:55

9dd3c5 sta $0100,x [9d0104] A:200a X:0004 Y:0000 S:1bc8 D:0900 DB:9d nvmxdIzc V:248 H: 858 F:55

Breakpoint 3 hit (2)

9dd3c3 lda ($02),y [9df2c2] A:200a X:0006 Y:0002 S:1bc8 D:0900 DB:9d nvmxdIzc V:248 H:1014 F:55

9dd3c5 sta $0100,x [9d0106] A:200b X:0006 Y:0002 S:1bc8 D:0900 DB:9d nvmxdIzc V:248 H:1060 F:55

Breakpoint 3 hit (3)

9dd3c3 lda ($02),y [9df2c4] A:0002 X:0004 Y:0000 S:1bc8 D:0900 DB:9d nvmxdIZc V:248 H: 794 F:11

Ladies and gentlemen, we have ROM reads! Let’s immediately take a peek at ROM around 9df2c0 in the Memory Editor of the debugger.

Et Voilà! It’s not common to get this much information from a single peek in memory, but here the “text” storage is pretty much laid out in front of our eyes. Note that the data rendered in blue are addresses read or written at this point in the debugging session.

- From

9DF2AC(be 20…): List of tilemap values for the upper half of the characters. - From

9DF2D4(10 20…): List of tilemap values for the lower half of the characters.

And what may the other blue block at 9DF292 (ac f2…) be? Reading the values as 16-bit words, the first two values are F2AC and F2D4. That’s the lower 16 bits of the addresses to the tilemap lists above! The next value, 000A, is surely not an address though. But looking at the first line of text when it is fully rendered, we can see that it’s 10 characters long… Coincidence? Changing the value to something lower, say 4, and running through the screen again quickly proves that the value indeed is the list length.

Next steps

At this point we’ve traced the data from what is displayed on screen, to the data in VRAM and all the way back to ROM. Maybe a bit surprisingly, there’s no plain text strings stored but rather arrays of raw tile data. The developers probably decided that with so little text in the game, it’s simpler to bake the text into tile data as part of the build/tooling to save some run-time complexity. A game with more text would surely add another run-time step where text encoded as 1- or 2-byte characters are transformed to 2*2 tile map words.

In the next part we’ll add the information we gathered to our snestistics labels file, and trace back one more step to see where the pointers to the “string definition” data structures we just found come from!

To be continued…